In early 2008—on the brink of the second generation iPhone’s release—emergency medicine doctor Michael Omori unabashedly gushed over the digital upheaval he saw at the medical community’s fingertips: swipes on slim devices leafed pages of hefty medical books too cumbersome to tote on rounds. Thumb taps quickly summoned archived data into emergency rooms. And light pecks conjured 3D anatomy guides and pill identification tools at the bedside.

In a breathless letter to his colleagues in the Journal of Emergencies, Trauma and Shock, Omori scrolled through all this potential. The letter ended succinctly: “The future is now! Join the iPhone revolution.”

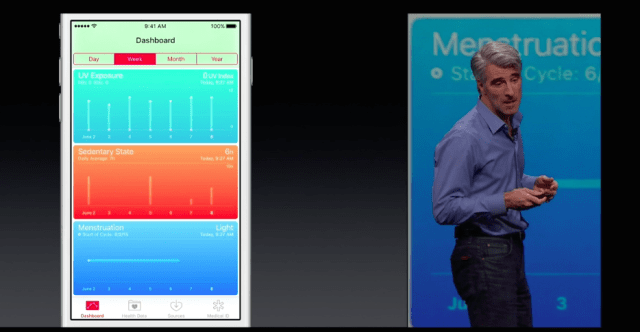

Ten years into that future, the revolution is still going strong, Omori tells Ars. In their decade of sinking into white coat pockets, iPhones have become embedded in medical education and practices. Pulling out an iPhone every now and then during a hospital shift is “basically the standard of care that’s out there,” he said. Yet, their role and capabilities continue to expand and evolve in doctors’ hands, as he and other experts told Ars. There have been hits and misses along the way, they note, but amid the coup of clinical norms, doctors await even more technological tremors. For instance, many foresee virtual reality-based tools for training surgeons or guiding patients through physical therapy, and they also foresee the coming of age of diagnostic tools powered by machine learning and other artificial intelligence. There’s also the transition of iPhones from doctor sidekicks to patient empowerment, via things like health tracking, HealthKit, and telemedicine.

As such, Omori’s enthusiasm hasn’t wavered in the last decade. To be fair, he is a self-described Machead, who bought Apple stock in 1987—so he’s slightly biased. But of all Apple’s products, it was the iPhone that shook up his career the most. Inspired by its effects, he left his assistant professor position at the University of South Florida shortly after writing the letter and became a medical informaticist.

Across the country, the iPhone had similarly strong sway on Robert Trelease. “I had this feeling at the beginning… it’s like the hair on my arms stood up,” the professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, recalls to Ars. As an established tech-enthusiast, he had also followed Apple closely. His first peek at the iPhone stirred memories of the Newton. Still, this new device was somehow different from anything else. And the feeling the iPhone gave Trelease was like the one he got the first time he had seen a PC, he said: “Whoa, this is going to change everything.”

Exam prep to exam rooms

Starting in 2001, UCLA required medical students to carry around PDAs packed with medical tools—a medical encyclopedia, drug dosing information, and clinical decision support software. But with the release of the iPhone, those PDAs were quickly ditched. By 2009, smartphones were the new requirement. And even as other brands came onto the market, Apple had a hold on students and doctors, Trelease notes. Over the years, about two-thirds of students seem to prefer Apple, he ball-parks. Looking to the class during lectures, “I see glowing apples,” Trelease says. He suspects the design and safety features play a role.

As students took up iPhones, Trelease—who teaches anatomy, neuroscience, and embryology—added app developer to his titles of doctor and professor. He registered as an Apple developer in 2008 and released the iPhone version of his book, Netter’s Surgical Anatomy Review P.R.N. in 2010. He has become a champion of e- and mobile-learning as well as an expert in how to best integrate and design smartphones and tablet resources for busy, always-moving doctors and students.

“The old philosophy for medical school is try to cram all those drugs, and bugs, and anatomy, and physiology, and biochemistry, and all those details into a student’s head in the first two years,” Trelease notes. Naturally, not all of that sticks. But now, there’s less emphasis on memorization. And with that out of the way, teachers can focus on “developing a basic framework that students can build on, and [students] get the information more progressively.”

Armed with mobile devices brimming with medical resources, students’ comprehension can click into place as they’re doing clinical rotations. That’s really where they learn “the final complex of social and biomedical knowledge, management, and judgment they need to deal with clinical problems,” Trelease notes. “A lot about being a physician depends on experience.”

The iPhone played a big role in refining that progressive learning strategy, he says. For instance, in the conclusion of a 2016 book chapter on mobile learning for surgical clerkship, he wrote: “The most striking qualitative lessons were directly related to exploiting the historically unprecedented, rapid evolution and widespread popular diffusion of smartphones and functionally related new mobile devices…”

iPhone, MD

The points are echoed by Omori, who notes that smartphones have been equally useful to practicing doctors long out of school. Pulling out an iPhone and looking up trial data or a reference is “basically applying evidence-based medicine for patient care rather than shooting from the hip.” Plus, smartphones are now so ubiquitous, doctors can connect with patients over their smartphones, showing each other the references and information they’ve both found—what a patient may have come across on a search or what a medical reference indicates.

Omori points to apps such as epocrates and Medscape, medical reference apps, and the 3D anatomy guides from Visible Body. “That stuff is really a help when it comes to explaining injuries,” he says. He also mentions clinical decision apps, such as MDCalc, which provides physicians with quick equations and algorithms to calculate things like stroke risk or assess if a patient can safely be sent home. These are merely a few of the plethora of medical apps now available.

Inspired by the development, Omori left his position in Florida a few years after his iPhone revolution letter and earned a degree in medical informatics at Northwestern. He now works as a consultant for hospitals on electronic medical systems, taking occasional clinical shifts on the side. The position has given him a good vantage to watch technology alter the landscape of medicine overall—from doctors’ daily decisions, to new equipment and hospital management.

Going to conferences and various hospitals, Omori tallied the technological casualties as well as the victors. Among the doomed were companies that tried to make medical equipment that docked with or physically locked onto iPhones. For example, some companies tried making a laryngoscope that physically pairs with an iPhone. The problem is, with each redesign, the dimensions of the phone change and the devices don’t perfectly fit together anymore. Hospitals or private practices could be out tens of thousands of dollars on a piece of medical equipment that has the lifespan of a smartphone model, he explains.

New drivers

Aside from these successes and failures, there have also been things in between—ideas that haven’t quite had their judgment day. Trelease looks forward to watching the evolution of AI-powered diagnostic tools and virtual reality-based applications in medicine, for instance. Omori says consumer health and fitness applications are “where it’s at,” and he has personal data to back up that projection.

Trauma-based life in the ER turned him into a “bloated tub of goo,” he laughs. With fitness apps on his phone, he has gotten the weight off and better managed his health. “I’m definitely healthier now than I was at 35,” he says. Such apps and applications have a ways to go before they’re integrated into medical practice, Omori says. And “any time you have patients entering their own data, it’s a box of chocolates,” he notes. Still, preventative medicine is better than expensive invasive medical interventions, and patients are motivated to take control of their own health—with the help of their phone.

Doug Fridsma, president and CEO of the American Medical Informatics Association, couldn’t agree more. He sees the next phase of the iPhone revolution as being in the hands of patents. “The phone I think has now become not just an extension of the doctor but an extension of the patient,” he told Ars.

He likens the shift to that of automobiles—horseless vehicles—at the turn of the twentieth century. At the time, doctors jabbered in medical journals over the ‘physician’s automobile.’ An article in a 1906 issue of JAMA, declared:

“To no class is the development of the automobile of more importance than to physicians. How to reach their patients in the quickest, surest, easiest and cheapest manner is a practical problem to them.”

Of course, after the 1908 release of the affordable Ford Model T, the role of the automobile changed, Fridsma notes. In the same way, he sees iPhone’s medical utilities switching hands. For instance, he chose his current healthcare provider because of their app. “It allowed me to schedule appointments, refill prescriptions. My current provider does Facebook consultations on the weekends and evenings, and I can do it all on my phone,” he says.

Echoing Omori, Fridsma says that giving patients more access and control over their healthcare is certainly a plus. Beyond that, a key benefit is that more patients can gain access to healthcare this way. People in low-income households may not have great insurance, ready access to clinics or academic researchers, or a computer—but they likely have a smartphone, he says. With the ubiquity of iPhones and the endless array of similar devices it has inspired (plus the development and advancement of telemedicine), there’s a renewed chance to address some of the country’s massive healthcare inequalities.

“Economic disparities notwithstanding, if people of every income bracket have access to mobile technology through smartphones, they now have access to the Internet, to these apps, to doctors, to research… all of those things become something that in the past they really didn’t have access to,” he said. “The real transformation with the iPhone, we’re just beginning to see now.”